SYNOPSIS (via the publisher)

“This is a book about Heaven,” says Jayber Crow, “but I must say too that . . . I have wondered sometimes if it would not finally turn out to be a book about Hell.” It is 1932 and he has returned to his native Port William to become the town’s barber.

Orphaned at age ten, Jayber Crow’s acquaintance with loneliness and want have made him a patient observer of the human animal, in both its goodness and frailty.

He began his search as a “pre–ministerial student” at Pigeonville College. There, freedom met with new burdens and a young man needed more than a mirror to find himself. But the beginning of that finding was a short conversation with “Old Grit,” his profound professor of New Testament Greek.

“You have been given questions to which you cannot be given answers. You will have to live them out—perhaps a little at a time.”

“And how long is that going to take?”

“I don’t know. As long as you live, perhaps.”

“That could be a long time.”“I will tell you a further mystery,” he said. “It may take longer.”

Wendell Berry’s clear–sighted depiction of humanity’s gifts—love and loss, joy and despair—is seen though his intimate knowledge of the Port William Membership.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1. INTERPRETING FICTION - The book begins with this notice: “NOTICE - Persons attempting to find a “text” in this book will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a “subtext” in it will be banished; persons attempting to explain, interpret, explicate, analyze, deconstruct, or otherwise “understand” it will be exiled to a desert island in the company only of other explainers. BY ORDER OF THE AUTHOR.”

Why do you think this notice was included? How do you think it should affect the way we discuss this book?

2. CONVERSIONS - As a way of remembering some of the book, Jayber seems to go through a number of turning points, or conversions: What were some of these?

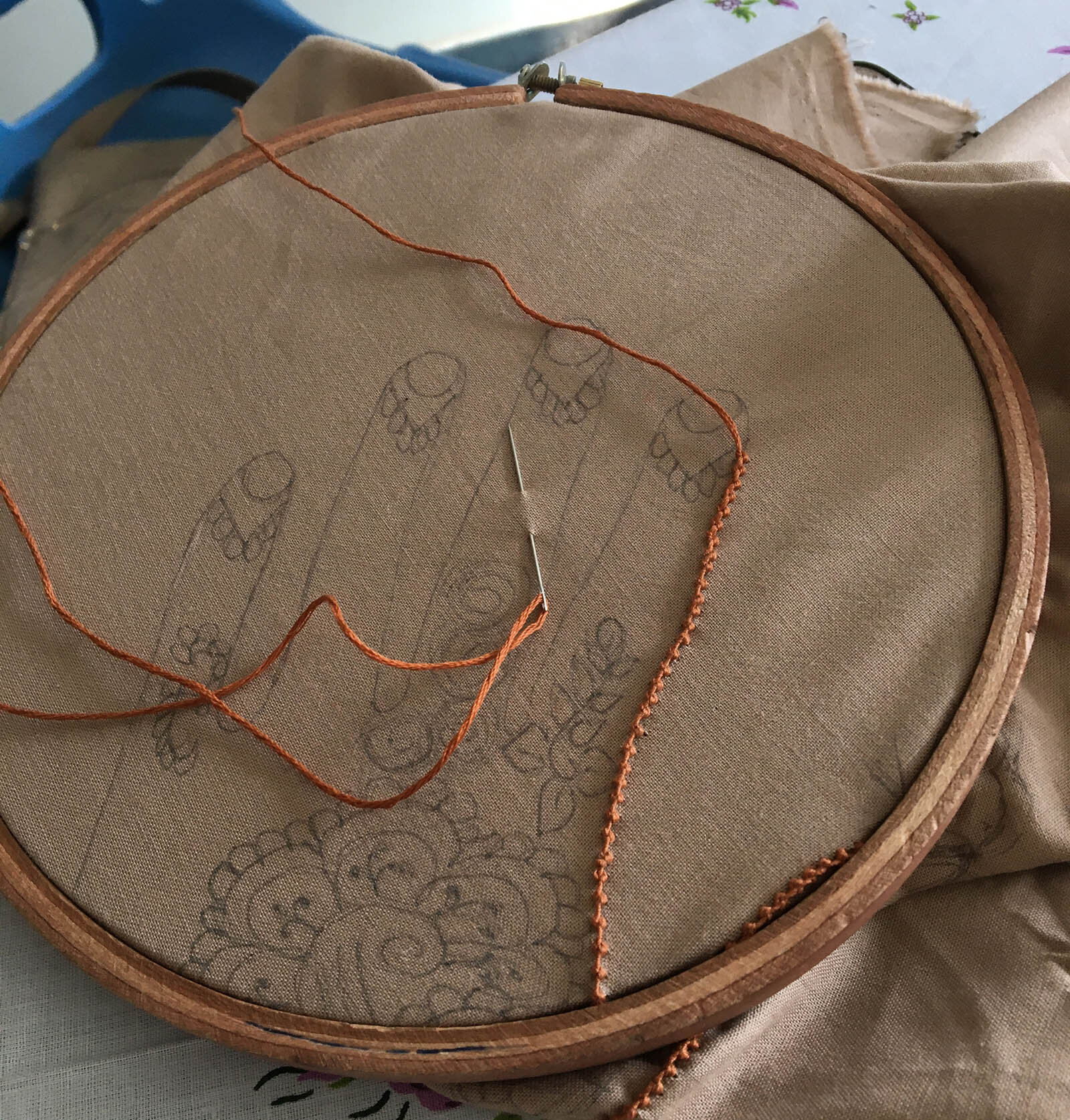

3. PLACE - So much of the book is about place. After he determines to go home to Port William, the world Jayber inhabits is all sacred. He writes, “And I knew that the Spirit that had gone forth to shape the world and make it live was still alive in it. I just had no doubt. I could see that I lived in the created world, and it was still being created. I would be part of it forever. There was no escape. The Spirit that made it was in it, shaping it and reshaping it, sometimes lying at rest, sometimes standing up and shaking itself, like a muddy horse, and letting the pieces fly.”

Is this familiar to you, or does it describe a different way of seeing the physical world?

4. TIME - Early in the book, Jayber describes reflections on the water. He eventually lives by the river watching the surface of the water. He connects with the river as a metaphor of past, present, and future. “The surface of the river is like a living soul, which is easy to disturb, is often disturbed, but, growing calm, shows what it was, is, and will be.”

This book has a long view of time and how individuals, communities, families, and places change over time. What did you notice about the passage of time in this book?

5. RELIGION - Jayber sees the world in a thoroughly Christian way, but he admits streaks of doubt and doesn’t think much of the rotating cast of preachers he hears in church. “To them, the soul was something dark and musty, stuck away for later. In their brief passage through or over it, most of the young preachers knew Port William only as it theoretically was (“lost”) and as it theoretically might be (“saved”).”

He also writes, “the belief has grown in me that Christ did not come to found an organized religion but came instead to found an unorganized one. He seems to have come to carry religion out of the temples into the fields and sheep pastures, onto the roadsides and the banks of rivers, into the houses of sinners and publicans, into the town and the wilderness, toward the membership of all that is here. Well, you can read and see what you think.”

What did you think of Jayber’s Christianity?

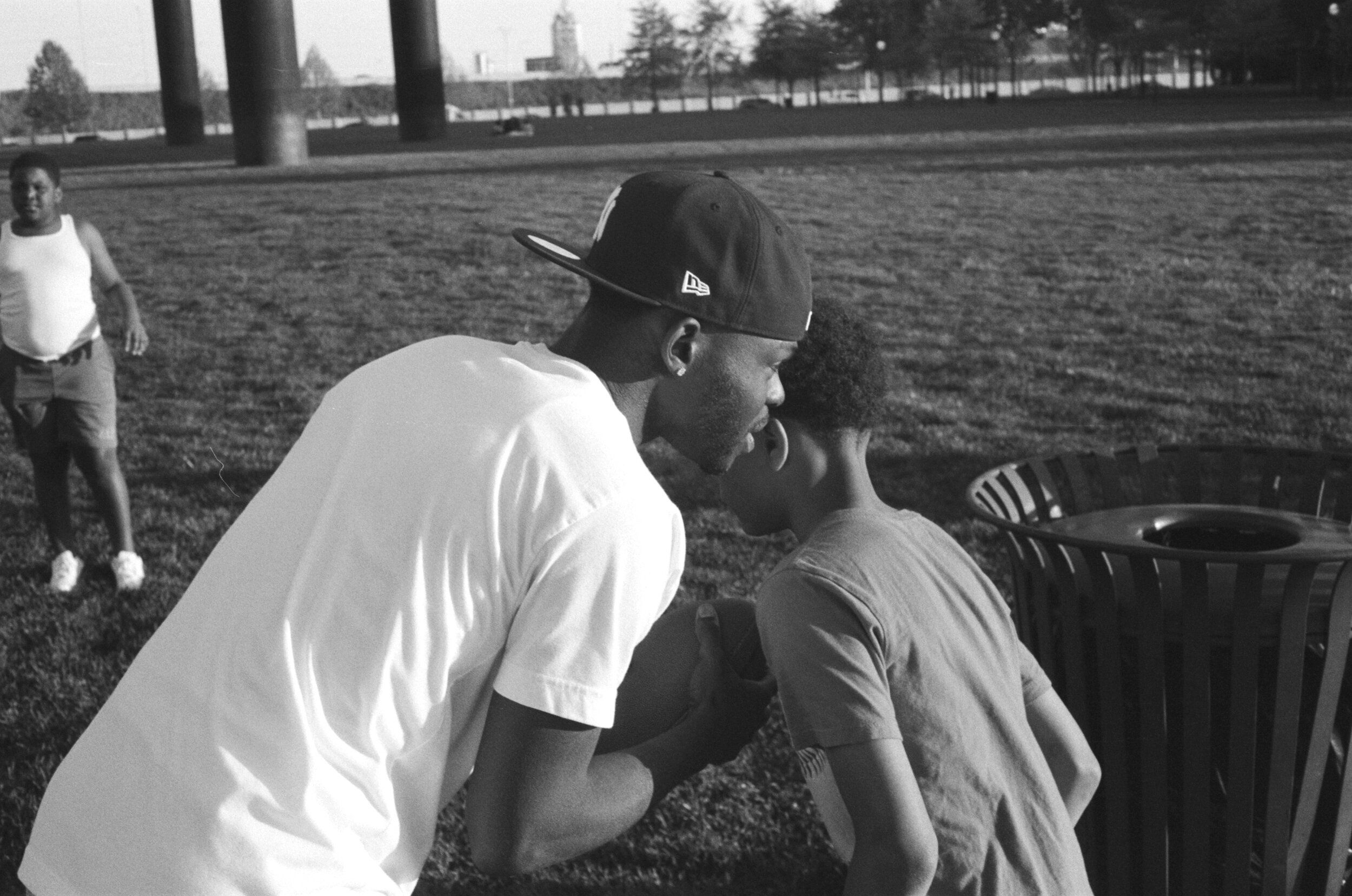

6. MEMBERSHIP - Jayber sees the people of Port William as belonging to the Membership. What can we learn from his understanding of a community?

7. WORK - Jayber dropped out of seminary and gave up his calling to become a preacher. In becoming Port William’s barber he fulfilled a unique social role and in his other work too. What roles did Jayber fulfill for his community?

8. THE NEWS, THE ECONOMY, AND THE WAR - Jayber is critical of the wars and the aggressive modern economy. What are examples of this, and what did you think of his ideas? Is he just an old crank? An idealist? Or did you find him compelling on these themes?

9. LOVE and FIDELITY - After Jayber sees Troy in Hargrave with another woman (not his wife Mattie), Jayber jumps out of the roadhouse’s bathroom window, abandoning Clydie to walk home. Why do you think he responded this way? What did you make of his “marriage” to Mattie?

10. HEAVEN - “This is a book about Heaven. I know it now. It floats among us like a cloud and is the realest thing we know and the least to be captured, the least to be possessed by anybody for himself. It is like a grain of mustard seed, which you cannot see among the crumbs of earth where it lies. It is like the reflection of the trees on the water.”

In what ways is this book about heaven? What do you think Jayber means?